The State of

the State of the Union

"[The President] shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union..."

Article II, Section 3, United States Constitution

In 2019, the State of the Union was in a state of uncertainty, due to, well, current American history. But from its inception, the address itself was in flux, from its date to its delivery.

First President George Washington started in 1790, delivering his and the nation's first State of the Union address in the Senate chamber of Federal Hall in New York. Senator William Maclay, not one for glowing praise, said of the event,

“The President was dressed in second morning, and read his speech well."

Washington delivered his address in person on January 8. So it began in January. Washington delivered his second State of the Union address--later that same year, on December 8. I don't have a clear answer as to why the date changed, but it stayed in the days just before winter (usually between November 22 and December 8) for the next 12 years. John Adams would have the pleasure of delivering the last SOTU in Philadelphia at Congress Hall, and the first SOTU address in Washington, D.C., in the work-in-progress Capitol building, on November 11, 1800.

It would be the last such address read in-person for over a century.

"The circumstances under which we find ourselves at this place rendering inconvenient the mode heretofore practiced of making by personal address the first communications between the legislative and Executive branches. I have adopted that by Message, as used on all subsequent occasions through the session."

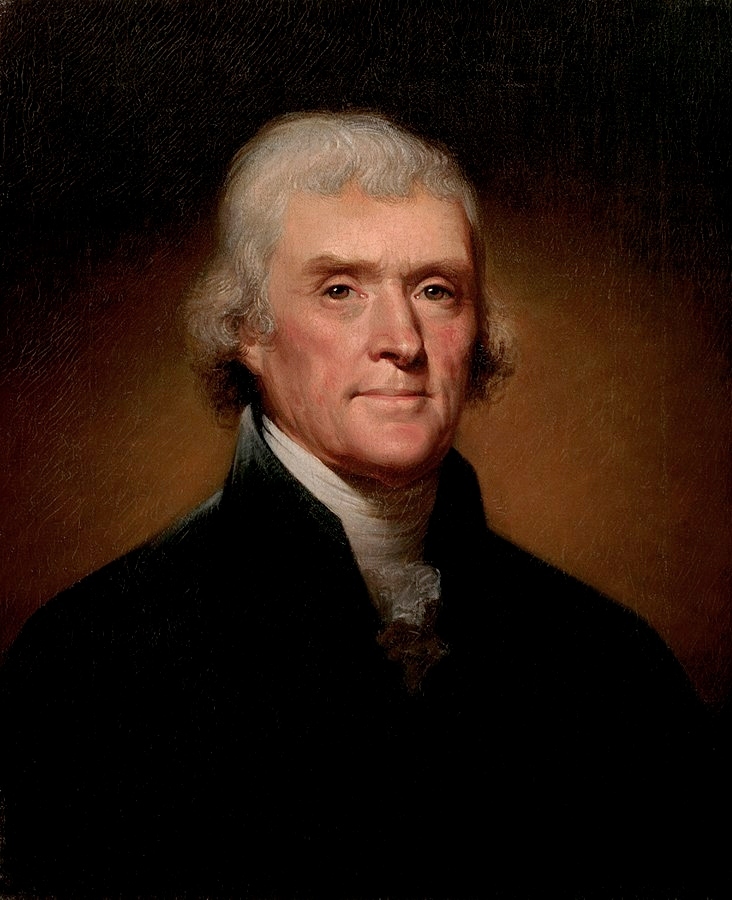

Thomas Jefferson, December 8, 1801.

In other words, no in-person address. Jefferson appeared to want a departure from public address. Some say it was to avoid a monarchical appearance. Some say he was just shy. Granted, his written addresses could run thousands of words long. Andrew Jackson took it to over ten thousand words.

Regardless, the tradition of a written State of the Union continued, even throughout the Presidency of the outspoken Theodore Roosevelt.

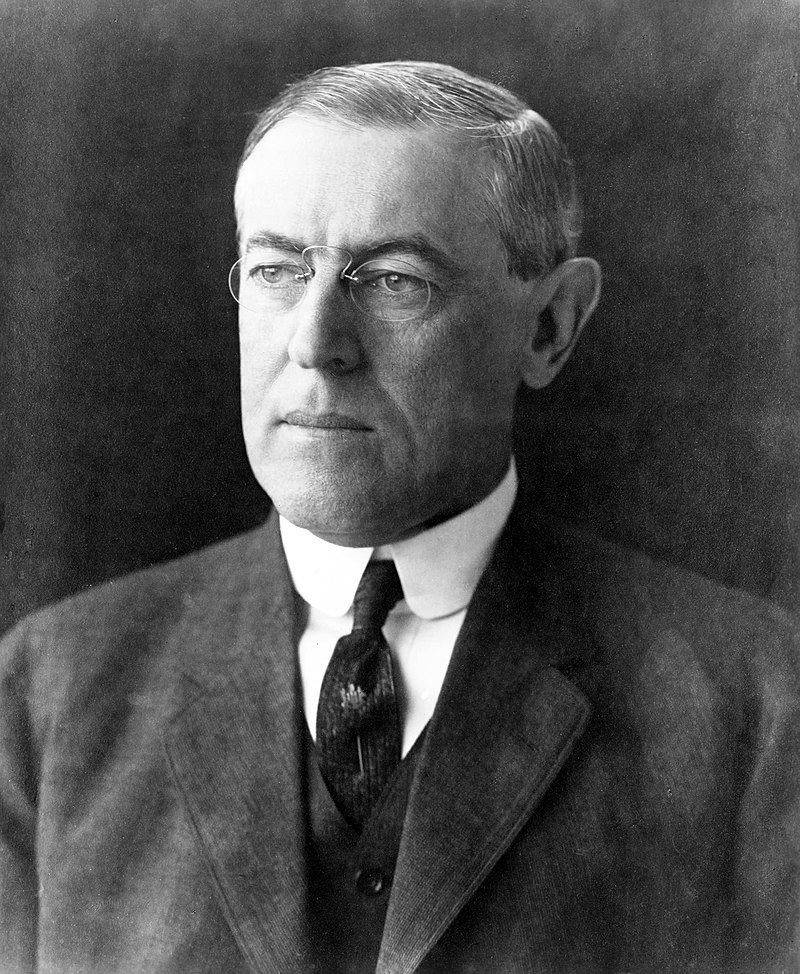

The man who changed it back? Woodrow Wilson.

According to an editorial in the Baltimore Sun, Wilson "believes it to be the dignified and natural thing to deliver his own message instead of sending the document by messenger from the White House and having it read by a clerk," which the editor agreed with - it took a while for the Congress to get used to the idea. But it did catch on, and in-person State of the Union addresses were back in "mode."

Take a look at the text in question of Article 2, Section 3 in its entirety. What do you think? Should any President give an in-person speech - or should it be limited to paper? (let's try and keep this non-political, please.) Leave your party-neutral comments below!

"He shall from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient; he may, on extraordinary Occasions, convene both Houses, or either of them, and in Case of Disagreement between them, with Respect to the Time of Adjournment, he may adjourn them to such Time as he shall think proper; he shall receive Ambassadors and other public Ministers; he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed, and shall Commission all the Officers of the United States."